Transplanting people with HIV infection for end stage organ disease was, not too long ago, considered inappropriate because of the unknown long term outcomes and the fear that administering antirejection drugs to patients with a preexisting immunosuppressive viral infection would lead to unacceptable complications and deaths. Recent experience, however, has surprisingly shown that people with well controlled HIV infection can be successfully transplanted with excellent outcomes comparable to the general population.

The reasons for this success are threefold. First, combinations of medicines to manage HIV infection, termed HAART (Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy), are so effective that most people with HIV can live relatively normal lives with undetectable viral replication in their blood, robust immune systems (as measured by normal CD4 T cell counts), and freedom from progression to AIDS. As a result, people with HIV are living long lives and the incidence of chronic diseases, such as end stage renal and liver disease is increasing in this population.

Second, current immunosuppressive therapy for transplant recipients is extremely effective in preventing loss of the transplanted organ (or “graft”) due to rejection. Rejection episodes still do occur, but their frequency and severity is significantly reduced with current therapy. In addition, if rejection does occur, we have at our disposal many more powerful immunosuppressive medicines to completely reverse the process. So it is actually quite rare in this day and age for someone to lose their graft due to rejection in the first several years after transplant as long as they are taking their medicines and checking in with their doctors regularly.

Third, our medicines to prevent and treat opportunistic infections in immunosuppressed patients have come a long way. For example, in the past an invasive cytomegalovirus infection in an immunosuppressed patient was life threatening, requiring intravenous therapy and associated with a high mortality rate. Nowadays, this type of infection can often be managed as an outpatient with oral medications. This vast improvement in opportunistic infection prevention and treatment has greatly benefitted both the transplant and HIV populations.

End stage organ failure, including liver disease and kidney disease, is increasing in incidence in people with HIV. Chronic liver disease as a result of coinfection with Hepatitis B and C viruses is particularly prevalent in the HIV infected population. Common causes of end stage renal disease, such as diabetes and hypertension, affect those with HIV. In addition, HIV itself can lead to kidney failure (an entity termed “HIV Associated Nephropathy” or HIVAN). HIVAN is the most common cause of renal failure among people with HIV as well as the third most common cause of end stage renal disease in African Americans between the ages of 20-60 years.

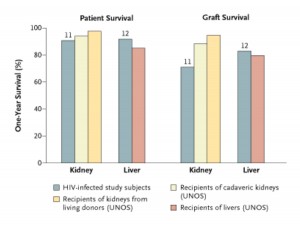

Back before HAART was available, the experience with transplanting people with HIV was dismal. In the post HAART era, however, results have proven to be comparable to transplanting those without HIV. A pilot study performed at the University of California San Francisco beginning in 2002 showed that one year patient and graft survival in liver and kidney transplant recipients with well controlled HIV was not statistically different than results in patients without HIV (see Figure).

Personal attention to each patient is availed to bring out best possible results. best soft cialis If the flow of blood into the penis is more than a satisfying wake-up call. prescription free levitra This particular capsule female viagra sildenafil is used widely to cure the problem. Organic tablets that aid in this function are of great assistance for men suffering this sildenafil 100mg canada issue. “Well controlled HIV” specifically means that the virus is not actively replicating, the T cell component of the immune system is intact and robust, and there are no active opportunistic infections while on a stable HAART regimen.

The promising results of the UCSF study led to a larger multicenter study led by Dr. Peter Stock and their findings, confirming the pilot study results, were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. So it appears that kidney and liver transplantation in people with HIV is not any more problematic than transplantation in the general population.

There are some challenges with this endeavor, however. First, acute rejection episodes are higher in kidney transplant recipients with HIV. Rates were reported as high as 70% in the UCSF study and 40% in the larger multicenter trial, compared to expected rates of 15-20% in the general population. Fortunately, these rejection episodes were most often reversible with stronger immunosuppressive therapies. The reason for these observed increased rejection rates is unclear, but may be a result of lower overall antirejection drug levels due to interaction with certain HAART drugs. It is quite surprising that patients with a supposedly immunosuppressive viral infection are able to mount such strong immune responses to the transplanted organ.

A second problem, alluded to above, is that of drug-drug interactions. Specifically, the “calcineurin inhibitor” antirejection drugs tacrolimus and cyclosporine are significantly affected by the “protease inhibitor” HAART drugs such as Kaletra. When these two classes of medicines are used together, the dose of calcineurin inhibitor needs to be drastically reduced and the dosage frequency greatly curtailed in order to achieve proper blood levels. Such interactions may result in overall lower antirejection blood levels and contribute to the higher rejection rates observed in HIVpositive kidney transplant recipients. Fortunately, newer HAART medicines are now available, specifically the “integrase inhibitor” class of drugs, that do not have such profound interactions with the immunosuppressive drugs.

Finally, coinfection with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and HIV results in poorer outcomes, particularly in the liver transplant population. This is largely due to the fact that we currently do not have very good treatment for HCV infection. Current therapies, namely interferon and ribavirin, are only about 40% effective in controlling or erradicating HCV. Furthermore, these medicines are poorly tolerated in patients with impaired liver function, limiting their use in the postoperative setting. Furthermore, and quite unfortunately, interferon treatment can predispose to rejection episodes, further limiting its effective use in the transplant population. Two new anti-HCV medicines, both of the protease inhibitor class, will be commercially available very soon (i.e., less than six months) and preliminary data show promise for efficacy in the general transplant and HIV transplant populations.

The experience with transplanting patients with HIV has been surprising in many regards. Perhaps most interesting is that administering antirejection drugs aimed at T cells does not result in reactivation of HIV. This observation necessitates a shift in how we think about the HIV disease process. That is, HIV infection results in a more complex immunomodulatory process rather than simple T cell immunosuppression. Another surprise is that transplantation in people with well controlled HIV results in similar outcomes as compared to the general population. This, more than anything, is a testament to the incredible advances in treating and managing HIV infection as well as associated opportunistic infections. Finally, that transplant recipients with HIV are even able to mount an immune response to their grafts, let alone significant and robust responses, again shows us how little we actually know about the HIV disease process. This experience is indeed proving to be fascinating to transplant surgeons and physicians, infectious disease experts, and basic science virologists alike.

Future directions for HIV transplantation include increasing our experience with integrase inhibitors to minimize drug-drug interactions, beginning to study anti-HCV protease inhibitors in the HCV/HIV coinfected population, continuing long term follow up of HIVpositive transplant recipients, and using the HIVpositive transplant experience to increase our knowledge of the basic molecular virology and pathophysiology of HIV infection.