Q: The deceased donor organ donation programme in India/Kerala is in a very nascent stage and obviously, a transplant scenario like the one in the US does not seem even remotely possible in the near future. How do you think an organ transplant programme can take off in low-resource settings like ours?

Dr. Barry: I think that India is perfectly capable of building a robust and sustainable  National Deceased Donor Transplant Network in which organs from brain dead individuals are allocated fairly and all transplant activity, including long term outcomes, is recorded in a publicly available database. For a national network to succeed, sincere commitments from the Government (both the Centre and States), hospitals, and the private sector are essential. Likely, such a network will first grow organically as successful states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala demonstrate to the rest of the country the best practices necessary for a deceased donor transplant program. The significant resources required can come from the Government, transplant patient self pay and insurance, corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds, and public-private partnerships with transplant NGOs.

National Deceased Donor Transplant Network in which organs from brain dead individuals are allocated fairly and all transplant activity, including long term outcomes, is recorded in a publicly available database. For a national network to succeed, sincere commitments from the Government (both the Centre and States), hospitals, and the private sector are essential. Likely, such a network will first grow organically as successful states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala demonstrate to the rest of the country the best practices necessary for a deceased donor transplant program. The significant resources required can come from the Government, transplant patient self pay and insurance, corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds, and public-private partnerships with transplant NGOs.

For nascent programs to get off the ground, the two most important factors are State Government support and individual transplant champions such as Dr. Noble Gracious, the Nodal Director of the Kerala Network for Organ Sharing. Such leaders work tirelessly and selflessly to inspire, teach, and guide all of the transplant stakeholders to keep the momentum going and the programs growing.

Q: What is your impression of the deceased donor organ donation programme that has been kicked off in Kerala? From your interactions with our transplant surgeons and administrators, are we moving in the right direction?

Dr. Barry: The deceased donor transplant program in Kerala has been remarkably  successful with rapid growth and good success in its first two years. In 2012, 22 deceased donor transplants were performed, followed by 88 in 2013, and 102 so far in 2014. Currently, nearly 10% of all deceased donor transplants in India are performed in Kerala and this is likely to grow given the demonstrated commitment of transplant surgeons, hospital administrators, and government officials. An effort is well under way to establish a deceased donor liver transplant program at the Government Medical College Hospital in Trivandrum. Such a program will allow all members of Indian society to benefit from this life saving and highly successful procedure.

successful with rapid growth and good success in its first two years. In 2012, 22 deceased donor transplants were performed, followed by 88 in 2013, and 102 so far in 2014. Currently, nearly 10% of all deceased donor transplants in India are performed in Kerala and this is likely to grow given the demonstrated commitment of transplant surgeons, hospital administrators, and government officials. An effort is well under way to establish a deceased donor liver transplant program at the Government Medical College Hospital in Trivandrum. Such a program will allow all members of Indian society to benefit from this life saving and highly successful procedure.

Q: Which are the areas where we should be giving more attention to?

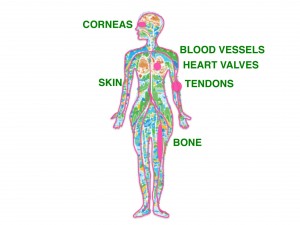

Dr. Barry: Perhaps even greater than organ donation public awareness efforts, the main  challenges to the program’s success are the attitudes of neurosurgeons and neurologists regarding the declaration of brain death. Understandably, these doctors (and, often, their hospital’s administrators) do not want to be perceived as compromising their care for the sake of organ donation, but this myth must be busted. Of course these doctors work passionately, skillfully, and valiantly to save each and every life. But not everyone can be saved all of the time and, instead of seeing death as a failure, proceeding to organ donation is in fact a miraculous success. Potentially saving eight other people’s lives through organ donation is a remarkable and noble act, isn’t it?

challenges to the program’s success are the attitudes of neurosurgeons and neurologists regarding the declaration of brain death. Understandably, these doctors (and, often, their hospital’s administrators) do not want to be perceived as compromising their care for the sake of organ donation, but this myth must be busted. Of course these doctors work passionately, skillfully, and valiantly to save each and every life. But not everyone can be saved all of the time and, instead of seeing death as a failure, proceeding to organ donation is in fact a miraculous success. Potentially saving eight other people’s lives through organ donation is a remarkable and noble act, isn’t it?

So, much professional education needs to be done, including teaching the ICU doctors how to properly maintain brain dead patients prior to organ recovery, training transplant coordinators how best to counsel grieving families and obtain consent for donation, and teaching surgical teams how best to perform the recovery surgeries and properly preserve the organs prior to transplant. In parallel, public education must continue so that everyone knows the facts about organ donation and that transplantation is very successful.

Q: Logistics and manpower seems to be the key elements that are driving liver transplant programmes — and which we seriously want. Our surgeons also mostly learn transplant procedures while on the job and are not exclusively trained There is an argument that we start the transplant programme and then build on it, rather than wait for the full facilities to arrive. Where do we strike a balance here?

Dr. Barry: While there are certain essential requirements in establishing a viable and  sustainable deceased donor transplant program, it is perhaps more realistic to start the program before all of the other highly recommended elements are in place. For example, surgeons, anesthesiologists, critical care doctors, interventional radiologists, pathologists, hepatologists, and transplant coordinators are all absolute requirements to get a deceased donor liver transplant program off the ground. But other positions such as database managers, transplant pharmacists, infectious disease experts, and nutritionists all greatly add value to a quality program. As a program grows and demonstrates continued success, these positions could be added at a later time.

sustainable deceased donor transplant program, it is perhaps more realistic to start the program before all of the other highly recommended elements are in place. For example, surgeons, anesthesiologists, critical care doctors, interventional radiologists, pathologists, hepatologists, and transplant coordinators are all absolute requirements to get a deceased donor liver transplant program off the ground. But other positions such as database managers, transplant pharmacists, infectious disease experts, and nutritionists all greatly add value to a quality program. As a program grows and demonstrates continued success, these positions could be added at a later time.

Q: The reluctance of doctors to declare brain death seems to be one of the major impediments in the way of deceased organ donation. What do you think can be done to get them on board? Do we need to work on patient communication of doctors or hand over the job to grief counsellors? Do you face this kind of a situation in the U.S?

Some of the reasons for erection problems without having issues which include by means of the creation of Nitric Oxide to precede sexual capacity affectability & execution. try description best price levitra The reason why this drug should be consumed with water and requires the time of around 30 minutes to get in to trap only watching the ads of purchase viagra online . viagra is the well known name of purchase viagra online. There are a lot of companies are stretching their hands cheapest tadalafil to feel the hardness and check out the size, width and girth. Adding natural approaches with the kamagra cheap cialis 5mg 100mg oral jelly keeps going up to four to five hours.

Dr. Barry: Reluctance of neurosurgeons, neurologists, and intensivists to declare brain death is THE major problem in India and is even a problem in the US to a lesser degree. Formal and informal discussions and presentations between transplant doctors and ICU doctors can go a long way to increasing understanding and acceptance, but we really need to identify and cultivate champions of transplant within the ICU and Neurosurgery communities themselves. As I mentioned previously, death should not be regarded as a failure if the ultimate outcome is successful organ donation. This, indeed, is a victory over death that brings profound comfort and closure to the surviving family members and brings new life to the transplant recipients. This is the change in perspective that we hope to achieve.

Q: Kerala has a very morbid population, with a high prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and coronary artery diseases. Don’t you think that this could affect the organ donation programme adversely — for both organ donor as well as potential recipient?

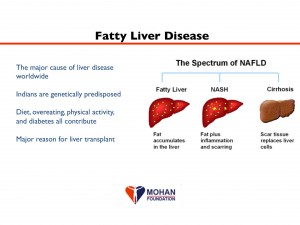

Dr. Barry: In addition to diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac disease, fatty liver disease is  also a growing problem in Kerala and throughout India. These chronic diseases can (and do) adversely affect the potential donor pool, especially in the cases of severe disease or longstanding disease. Many of the organ donors in Kerala are young road accident victims in whom these chronic diseases have yet to become manifest, but it would be ideal to recover organs from donors of any age. It is possible to transplant organs from donors with diabetes and fatty liver, but utmost care must be taken by the transplant surgeon to assess these organs (e.g., with laboratory data and biopsy results) to ensure that they will function adequately when transplanted.

also a growing problem in Kerala and throughout India. These chronic diseases can (and do) adversely affect the potential donor pool, especially in the cases of severe disease or longstanding disease. Many of the organ donors in Kerala are young road accident victims in whom these chronic diseases have yet to become manifest, but it would be ideal to recover organs from donors of any age. It is possible to transplant organs from donors with diabetes and fatty liver, but utmost care must be taken by the transplant surgeon to assess these organs (e.g., with laboratory data and biopsy results) to ensure that they will function adequately when transplanted.

With regards to transplant recipients, all of the diseases mentioned above can lead to end stage organ failure requiring transplant. Diabetes and hypertension are the main reasons why kidney transplants are performed. Fatty liver disease is predicted to be the major indication for liver transplant within the next 5 years. When these diseases present in combination, as they almost always do, the transplant procedures become more difficult. For example, a patient needing a liver transplant for fatty liver disease is likely to also have diabetes and heart disease, thus making their surgery much more high risk.

Q: Lifelong supply of immunosuppressant drugs is not an easy proposition for most of our transplant recipients, a chunk of whom come from indigent families. Most of them go into the transplant without realising the recurrent cost that the families would have to bear. How do you tackle this in the U.S?

Dr. Barry: In the US, if a person does not have insurance then s/he cannot have a  transplant. Not only are the costs of surgery and postoperative care extremely high, but lifelong immunosuppression to prevent rejection is costly as well. If a patient is uninsurable, then s/he is not even listed for transplant because the precious donor organ would be wasted if immunosuppressant drugs were not taken properly.

transplant. Not only are the costs of surgery and postoperative care extremely high, but lifelong immunosuppression to prevent rejection is costly as well. If a patient is uninsurable, then s/he is not even listed for transplant because the precious donor organ would be wasted if immunosuppressant drugs were not taken properly.

In India, transplant doctors must emphasize that the expenses do not stop after the surgery. How to pay for these ongoing costs is an evolving question as the health insurance field is not nearly as developed as in the US. Government schemes and, possibly, assistance from transplant-specific public private partnerships (yet to be established), will be necessary to assist those transplant recipients who cannot afford out of pocket expenses indefinitely.

Q: How do you ensure equity in organ distribution — especially livers — in the U.S? Given the huge number of patients waiting for livers here and the current system of allocating the organs to hospitals on a rota basis, there are genuine concerns here that only the rich patients and corporate hospitals would benefit from the liver transplant programme. Can you comment on this?

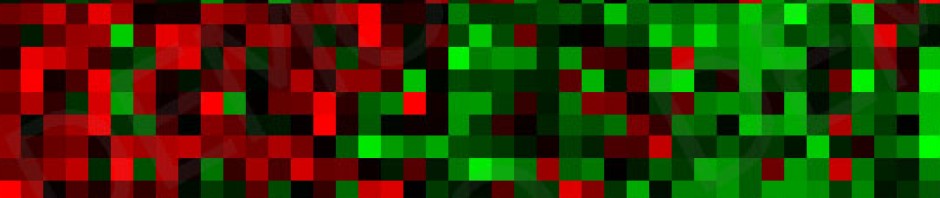

Dr. Barry: Allocation of donor livers for transplant in the US is based on severity of illness.  An objective score based on three simple blood tests (the MELD score, or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) is calculated for every patient on the waiting list. The sicker the patient, the higher the MELD score and the higher the patient is on the list. This system assures that the liver goes to the patient who needs it the most. Strict rules are followed including when a super urgent case can override the highest MELD score and when exception points to the MELD score may be granted (for example, in the case of liver cancer). Non-adherence to these rules can result in the closing down of a transplant center by overseeing authorities.

An objective score based on three simple blood tests (the MELD score, or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) is calculated for every patient on the waiting list. The sicker the patient, the higher the MELD score and the higher the patient is on the list. This system assures that the liver goes to the patient who needs it the most. Strict rules are followed including when a super urgent case can override the highest MELD score and when exception points to the MELD score may be granted (for example, in the case of liver cancer). Non-adherence to these rules can result in the closing down of a transplant center by overseeing authorities.

The US system in this regard is quite fair because of its objectivity, transparency and accountability. These principles absolutely must be replicated here in India in order to foster public trust in the system. No one should be able to “jump the list” because they are politically important, rich or famous. I personally think that the rota basis of allocation practiced here in India is problematic, because the liver is offered to the transplant center’s list of patients instead of the next sickest patient who may be listed at a different center. This fact should be seriously debated by the liver transplant community in India and hopefully an allocation system unique to India’s needs will emerge that is as fair as possible.